“I’m an impact investor.”

More and more, our fellow venture capitalists are introducing themselves this way. In recent years, “doing well while doing good” has grown from a trend to a full-blown mainstream movement. Firms, new and old alike, are embracing the model of generating positive social impact alongside financial returns. This is great news, right?

Not necessarily. These days, when we hear that someone is getting into the impact investment space, it raises questions.

All businesses have impact.

This is a fact that is simultaneously self-evident and often overlooked. Some businesses have a positive impact, some have a negative impact, and others have a little of both. Historically, most impacts have been externalities — pollution, obesity, widening inequality, etc. — the direct results of specific business practices, but never measured in company financial statements.

In addition, we don’t always share an understanding of which impacts fall into a positive or negative bucket. For example, a number of VCs call themselves “impact investors” because of the sector they invest in. If you invest in edtech or healthcare IT, for example, are you by default an impact investor? The truth is that many new businesses in these sectors may actually widen gaps between the haves and the have-nots, which in our view creates a negative overall social impact.

Take healthcare IT, for example. Innovation is exploding with a wide range of tech tools that aid diagnoses, treatment, and pain management, but most are only available to those who can afford it. These would be examples of gap-widening business models, in which the affluent can buy better products or services than their less well-off peers. Such advances are contributing to a growing gap in life expectancy by income.

This is similarly problematic in sectors like edtech, where expensive tools and apps give privileged students an edge all throughout their academic experiences, including at getting into selective colleges. Merit doesn’t earn the reward; privilege allows it to be purchased.

If a company is widening gaps in access and opportunity, or providing a strategic advantage to wealthy people over the poor, it’s not a positive impact investment.

We believe in gap-closing impact.

At Kapor Capital, we define impact as “gap-closing” technologies, particularly as they apply to low income communities or communities of color. Our investment criteria lay this out in three ways:

1. Closing gaps in access.

Some healthcare IT and edtech tools can provide unfair advantages to the elite, but there are a number of companies in these sectors who employ a gap-closing business model.

PreK12 Plaza, for example, creates dual language learning experiences for immigrant parents and children. One unique problem in the immigrant community is the language divide between generations. Children speak English all day in the classroom, and the language barrier often prevents parents from helping them with their homework. PreK12 Plaza helps translate curricula in 25 languages, so that parent and child can work together on homework, and teachers and parents can communicate on students’ progress, helping bridge both the language and educational divides.

Equally important, PreK12 Plaza sells its products to schools, using federal Title I funds, making it available to teachers, parents and students who most need it. It’s a rapidly growing company that democratizes access to an important service, rather than selling it to affluent families one by one.

2. Closing gaps in opportunity

Not everyone has an equal shot at landing a job, no matter how qualified they might be. Years of research show that the recruitment and hiring process is riddled with biases — often unconscious — that favor men over women, or white people over candidates of color.

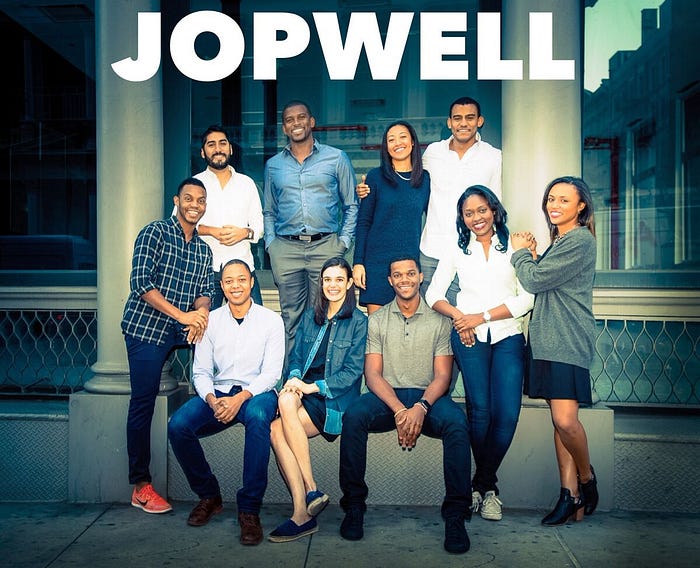

Fortunately, the fast growing People Ops Tech sector is coming up with innovative ways to mitigate these problems, and narrowing the opportunity gap. Companies like Interviewing.io provide an anonymous platform for technical interviews (including voice-masking), allowing applicants to compete solely on their coding skills — i.e. merit. Unitive helps hiring companies identify and correct biased language in their job descriptions that often discourages women or people of color from applying. Jopwell is a recruiting platform that helps companies expand their search pool to include more underrepresented candidates of color.

3. Closing gaps in outcomes

It can be expensive to be poor. Many companies that service the poor and working classes charge fees that are extraordinarily higher than similar services for the wealthy. The short-term or “payday” loan business is notoriously predatory. Short-term loans are often necessary for families living paycheck to paycheck, but many storefront loan operators intentionally trap their clients in debt cycles, in which they are taking out more loans just to pay back the interest on the first. In our portfolio, the company LendUp provides short-term loans that also provide a path out of high interest rates and into rebuilding one’s credit score.

Similarly, the international money transfer sector is a several hundred billion dollar market, fueled largely by working class immigrants providing support to their loved ones back home. While transfer fees can be exorbitant, companies like Regalii are providing an affordable, safer alternative.

Investing in gap-closing ventures often times means investing in diverse entrepreneurs.

Lived experience matters.

There are plenty of recurring themes within our gap closing companies. One important one is that many are founded by entrepreneurs who have experienced a real-world problem, and then invented a profitable tech solution to solve it.

For example, our edtech company, PreK12 Plaza, was founded by Ana Roca Castro, a Dominican national who experienced the education gap first hand when she immigrated to New York City as a teenager. While she had taken calculus in her homeland, she was assigned to remedial fourth grade math in her New York public high school. The teachers assumed that because she was an English language learner, she must not be smart. Her own lived experience — and the memory of her frustration and humiliation — inspired her to found a company that would solve that problem for hundreds of thousands of immigrant children.

Similarly, as a Black entrepreneur Jopwell CEO and Co-Founder Porter Braswell saw first-hand the biases in hiring and recruitment that were filtering people of color out of the pipeline. Also, the entire founding team of Regalii is comprised of immigrants who experienced the expense and security problems associated with sending remittances home.

These experiences show that diverse founders aren’t just a nice thing to have in your portfolio; they often provide a unique business edge. Founders with diverse lived experience can identify problems that are begging for a tech-driven solution.

Building a pipeline of diverse entrepreneurs

In Part I of this series, we explored how investors can take diversity seriously, primarily by starting with diversity on their own investment team. Building diverse investment teams, we noted, “puts you in the best position to expand your deal flow, discover promising new solutions and markets, and support your portfolio companies in the early implementation of their own diversity initiatives.”

If we are serious about this, it’s also crucial that we invest in the pipeline programs that create the diverse entrepreneurs of the future.

For the past 14 years, our nonprofit Level Playing Field Institute has sought to close gaps in the pipeline by operating rigorous STEM-focused college prep programs for low-income students of color.

Our SMASH (Summer Math and Science Honors) Academies provide an in-depth five-week, three summer STEM program that matches underrepresented students with the academic and technical training, resources, role models, and connections they need to pursue their dreams. Ultimately, we want to ensure that every student has a chance to make an impact in the 21st Century economy.

SMASH has been successful because it’s based on the research around what helps underrepresented students succeed.

This goes far beyond what the scholars are learning. We make sure that the teachers and mentors come from underrepresented backgrounds themselves, so young people of color see role models that look like themselves thriving in STEM.

The students stay on campuses like Cal Berkeley, Stanford and UCLA for a reason. Many are first-in-their-family college students, so living away from home navigating a sprawling campus can be intimidating enough to disrupt the learning process. These pressures can cause smart students to drop out, regardless of their ability to handle the coursework. SMASH not only prepares students for top-level STEM achievement, but underscores the fact that they belong in college.

We know about many of the challenges to college persistence, including social belonging, imposter syndrome, and the need for role models, because there is a body of academic research that explains them. But this research is nowhere near complete.

To understand all of the leaks in the tech pipeline, we’ve got to make an investment in the research that explores the leaks, and designs interventions to fix them.

Genius is evenly distributed throughout the population, but opportunity is not.

As investors, we have a role in creating opportunity for underrepresented geniuses — founders whose companies are informed by their diverse backgrounds and experiences. With the right amount of cultivation, an investment in the pipeline, and a focus on gap-closing technologies, we can simultaneously transform Silicon Valley and solve many of society’s most urgent social problems.